In late November 2025, a cataclysmic hydrometeorological disaster struck the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Torrential rainfall, associated with Tropical Cyclone Senyar, occurring during the peak of the monsoon season, triggered catastrophic flash floods and landslides across the provinces of Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. As water levels rose rapidly, entire communities were hit by sudden flooding and collapsing terrain, marking one of the most destructive weather events Indonesia has experienced in years.

Several other countries in Southeast Asia, including Sri Lanka and Thailand, have been hit hard by storms and floods, associated with the Cyclones Senyar and Ditwah.

Human Toll

At least 977 people have lost their lives, with hundreds still unaccounted for, according to initial compiled reports from publicly available disaster tracking sources, such as National Disaster Management Authority (BNPB), as of December 10th.

More than 1.2 million residents were evacuated, and millions of people have been directly impacted by widespread flooding and landslides.

Although the immediate threat and rains have passed, thousands are injured, and entire villages face the devastation of infrastructure, homes, crops, and livelihoods. Countless residents have been left without homes or family support, and many are injured, sick, and running out of food and water.

A Message from SeaCras

On behalf of SeaCras, we extend our deepest condolences to all those affected by this tragedy — to the families mourning their loved ones and to entire communities now facing the daunting task of rebuilding.

We recognize the scale of suffering and disruption that these floods and landslides have caused. To support recovery efforts, we are offering our before-and-after satellite imagery geospatial analysis that includes both landcover changes and sediment dispersion in the nearby sea. We are giving this to any organization, authority, or humanitarian partner engaged in response work. Our data is available to help:

- Map the most damaged areas

- Prioritize relief routes and resource allocation

- Assess infrastructure loss and plan reconstruction

- Document environmental changes for future resilience planning

If you are coordinating relief, planning reconstruction, or directing aid — please reach out, and we will work with you to put this data to use where it’s needed most.

You can download images in full resolution HERE.

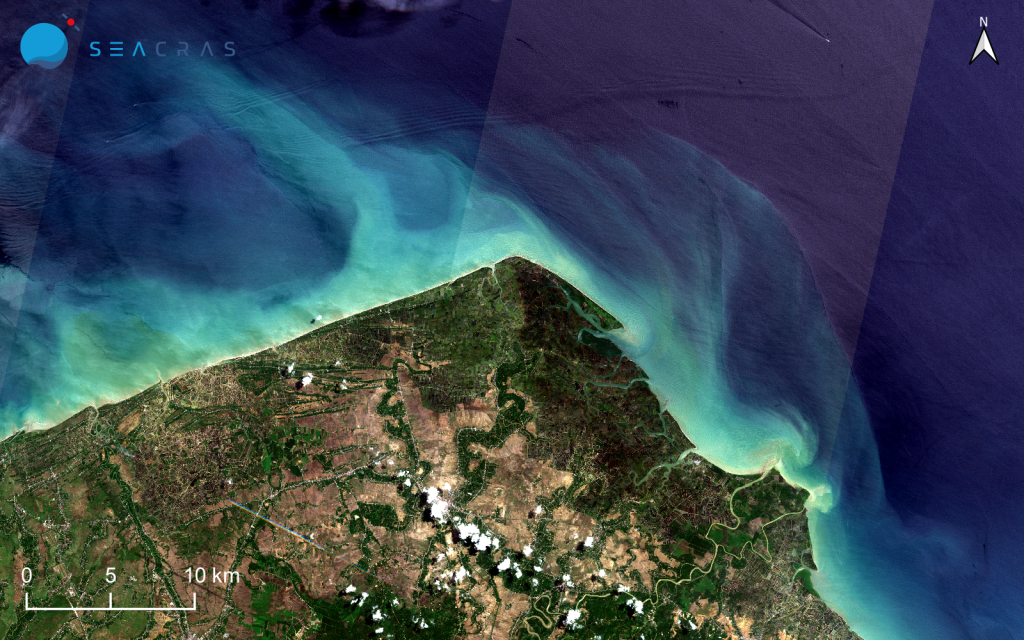

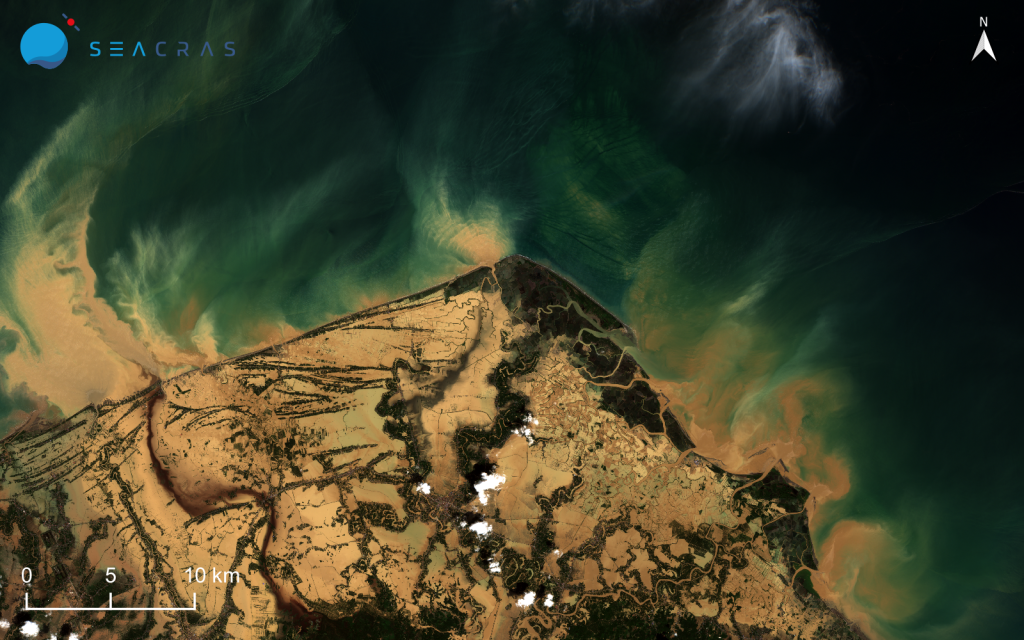

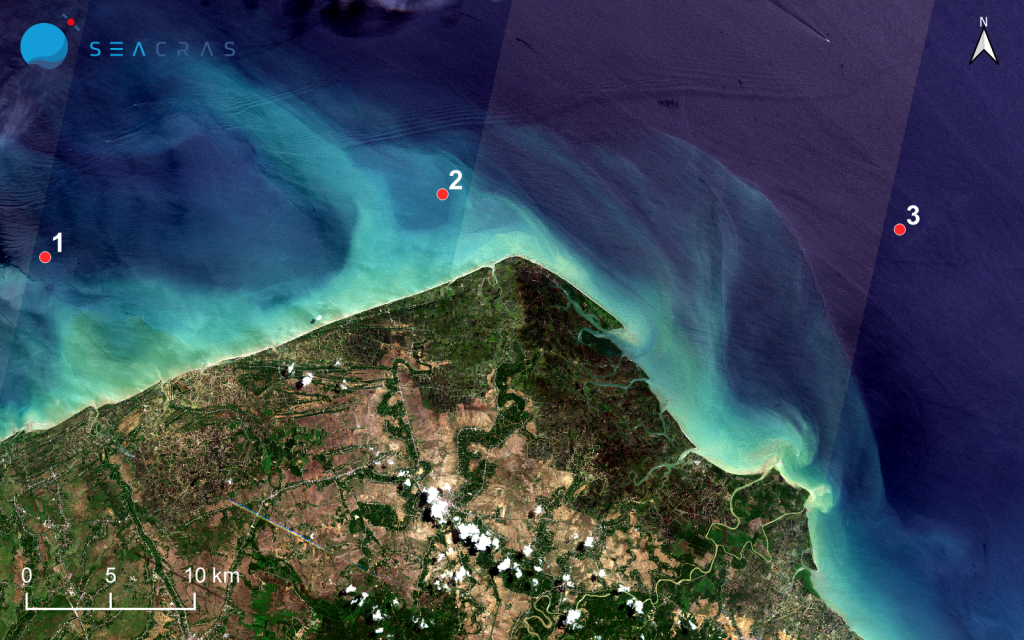

Figure 1. The RGB satellite image of the Aceh region. a) Left image: before the flood, 28/05/2025; b) Right image: after the flood, 29/11/2025.

Sources of satellite images: © ESA / Copernicus Sentinel-2.

Now let’s look at what unfolded, and how it is visible through the satellite images:

Figure 1. captures the Aceh region before the flood (left image), an unprocessed RGB satellite view from 28 May 2025, showing a coastline and marine environment in a relatively stable state. As it can be seen, land vegetation is moderately dense, with river fluvial discharges being a moderate influence to the surrounding Andaman sea.

The contrast becomes striking in the post-event imagery. Figure 1, right image, taken on 29 November 2025 — just a few days after the disaster — shows the same region after the flood, where visible changes along the coastline point to the scale of the disturbance. Landslides have completely demolished the landscape, changed the coastal line, and caused enormous sediment dispersion into the marine environment.

But how does this flood-induced landslide impact the Andaman sea?

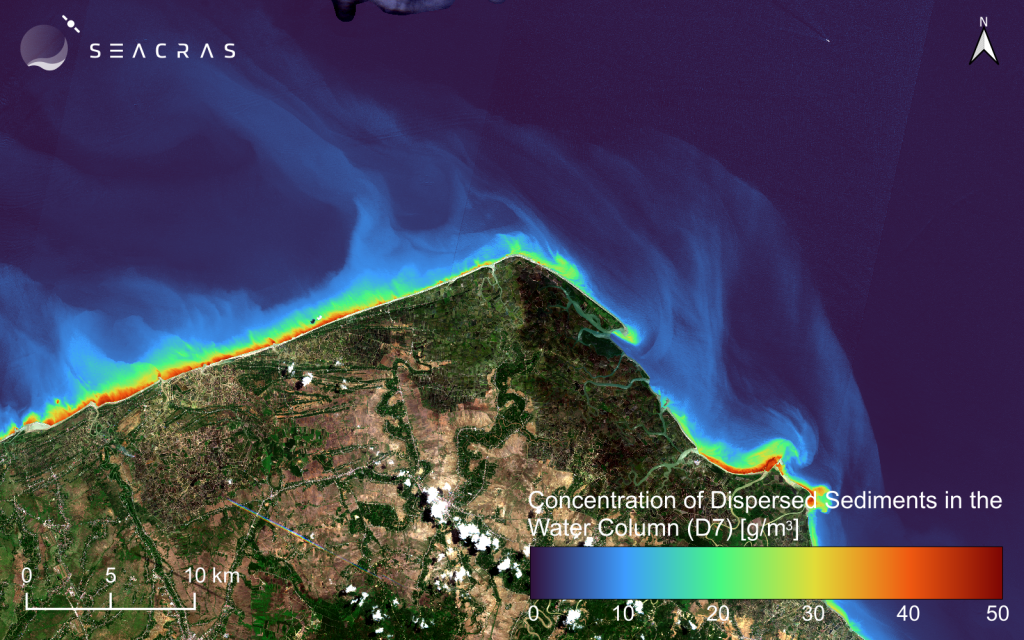

The answer can be found in SeaCras calculation of water quality parameters of the Andaman sea. SeaCras used its Coastal Intelligence software package to calculate values of dispersed sediments in the sea surrounding the island before and after the flood. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The processed satellite images, where the sea area is shown as a map of calculated concentration of dispersed sediments. a) Left image shows the processed satellite image of the Aceh region before the flood, 28/05/2025; b) Right image shows the RGB satellite image of the Aceh region after the flood, 29/11/2025.

Sources of satellite images: © ESA / Copernicus Sentinel-2.

In Figure 2, on the left, we can see the calculated concentration of dispersed sediments in the surrounding sea, reflecting normal conditions driven by routine fluvial discharges typical of the dry season in Southeast Asia.

In the right image, we can see abnormally high concentrations of dispersed sediments throughout the water column of the adjacent sea. These elevated values are a direct consequence of the abrupt flooding, vividly demonstrating how extreme events can rapidly transform both land and marine systems.

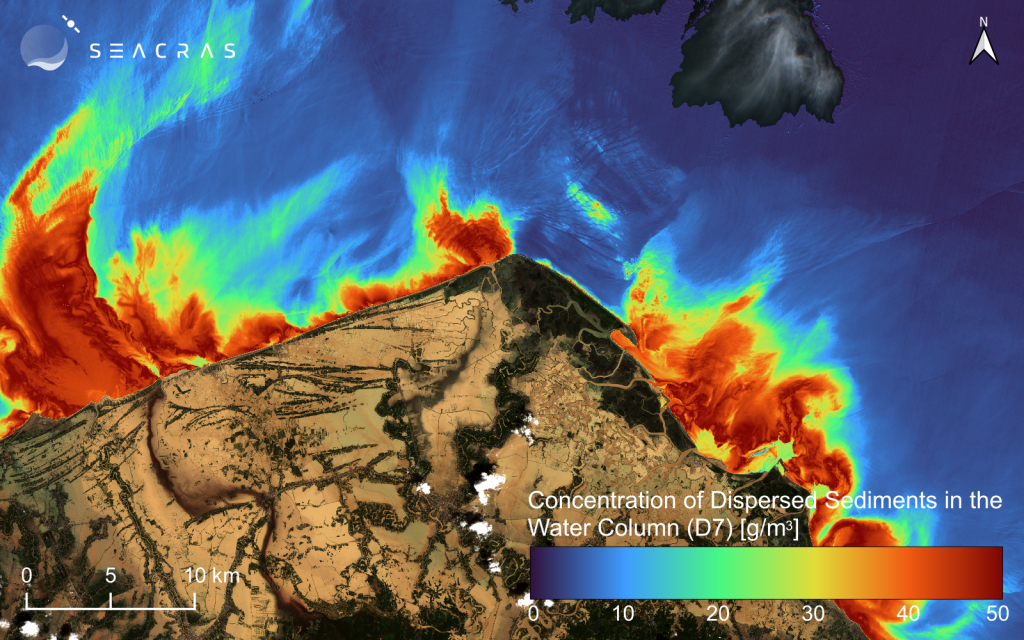

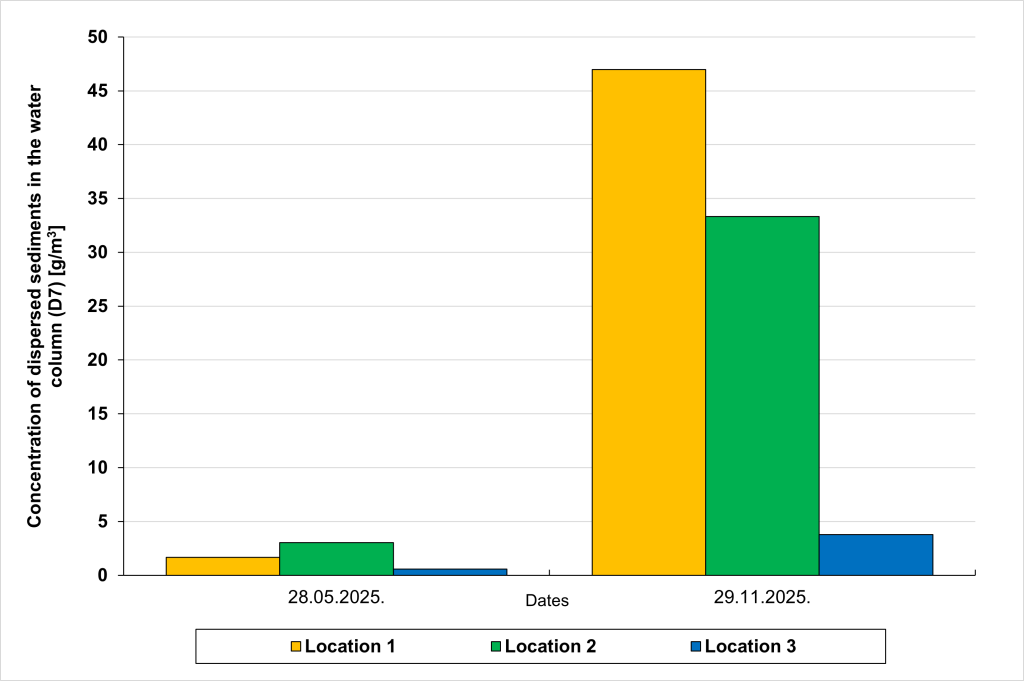

Figure 3. Microlocation analysis and comparison of dates with ‘normal’ values, resulting from usual fluvial discharges during the dry season in Southeast Asia, dated 28/05/2025, and b) the ‘abnormal’ values, resulting from abrupt flooding, dated 29/11/2025.

Sources of satellite images: © ESA / Copernicus Sentinel-2.

In Figure 3, we compared values of dispersed sediments for three (3) distinct locations before and after the floods. The results show striking sediment dispersion over a thousand of square kilometers of the surrounding sea, with values skyrocketing to 50 times higher than normal, even as far as 10 km from the coastline. This points to a large-scale change of biodiversity and habitat not only on land, but in the sea as well.

What Happened… and Why?

Days of extremely heavy rainfall, far stronger than what is typical even during the monsoon, soaked the ground and caused rivers to overflow across Sumatra. At the same time, a rare cyclone formed unusually close to the equator, adding even more rain and overwhelming both natural waterways and man-made drainage systems.

As water rushed downhill, it tore through towns, swept away entire villages, and buried communities under mud. Roads collapsed or disappeared underwater, leaving many areas completely cut off. Survivors in isolated regions went days without clean water, food, or medical help as the risk of disease and hunger quickly increased.

Underlying Factors

Experts note that, while the immediate cause was extreme weather, the severity of the disaster was amplified by ecological vulnerability — including deforestation, soil degradation, and loss of natural water retention in upstream areas that normally moderate flood impacts.

Was This Connected to Climate Change?

Climate scientists warn that climate change is making extreme rainfall events far more intense and frequent, and Tropical Cyclone Senyar is a clear example of this trend. Senyar formed in the Strait of Malacca, a region so close to the equator that cyclones almost never develop there, making the storm highly unusual.

Warmer oceans and a warmer atmosphere — both driven by human-caused climate change — allowed the storm to hold far more moisture, leading to record-breaking rainfall and severe flooding across Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand.

Early attribution studies suggest that these elevated temperatures likely intensified Senyar’s rainfall and destructive power. Even if climate change doesn’t always increase the number of storms, warmer oceans and air hold more moisture meaning storms produce heavier rain and more flooding than they used to — a pattern seen in Senyar and the associated monsoon extremes.

What is to be expected?

Recovery will be a long and complex process. The Indonesian government estimates that over $3 billion USD will be needed for reconstruction and relief across the hardest-hit regions.

Critical needs include:

- Clean water, food, and medical support for displaced families

- Restoring access to isolated communities

- Rebuilding homes, bridges, schools, and critical infrastructure

- Ongoing disease prevention and health care services

How Climate Change Hits Vulnerable Communities First

Climate change does not affect all people in the same way. Low-income and marginalized communities are hit the hardest, because they often have fewer resources, weaker infrastructure, and a larger dependence on natural resources like local land and water for daily survival. Many also live in high-risk areas, simply because safer land is unaffordable or unavailable.

So when disasters strike, they lack the means to prepare, recover or adapt. This deepens existing inequalities, pushing people even more into poverty as livelihoods, homes, water supplies, and food systems are destroyed.

International research shows that low-income populations are disproportionately exposed to climate hazards and less able to cope with loss or rebuild, whereas wealthier countries and communities can invest in more resilient infrastructure, early warning systems, and recovery.

But children bear the heaviest toll, as their bodies are still developing, making them more vulnerable to illness, malnutrition, and injury when disasters strike. Floods and storms often cut off clean water, healthcare, and schooling. Since they depend on adults for safety and support, any disruption leaves them exposed to greater risk, and the impacts can follow them throughout their lives.

This catastrophe is not only a story of devastating weather, but a warning of what a warming world can bring. Recovery must be matched with action — to protect people, strengthen ecosystems, and prevent future extremes from becoming even more deadly.